« Back to Glossary Index

Categories: Alphabet, Environment

Synonyms:

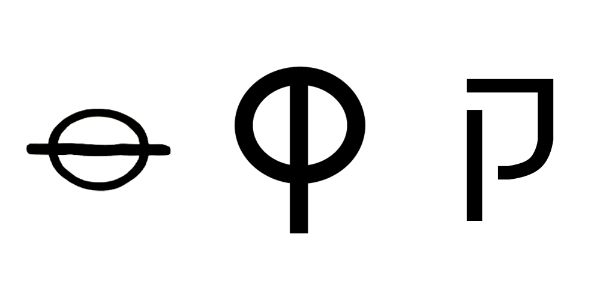

𐤒

The letter qauaph (𐤒) or Q/q is the nineteenth letter in the Afroasiatic language known as Paleo-Hebrew (Ābarayat). The letter has been equated with the letter Q and is used to replace most of the hard letter K placements in the English language. Nonetheless, the letter Q is the more accurate letter but was more than likely pronounced similarly to the modern letter K in the English language.

Extended Study for 𐤒 (q)

To read the study guide entry that elaborates on 𐤒 (q) then join our Extended Study Membership at https://www.paleohebrewdictionary.org/extended or use phdict.org/extended to share a short link with others.